Skin cancer can be deadly, and the numbers in New Zealand are sobering. According to Dr Andrew MacGill, of Skincheck in Auckland, “Skin cancer, including melanoma, is the most common cancer in Aotearoa New Zealand. Around 3,000 people are diagnosed with invasive melanoma, which is the most serious type of skin cancer. More New Zealanders die from melanoma than die on our roads—it tragically accounts for over 300 deaths a year.” While we can all see the impact of our harsh New Zealand sun on our skin with wrinkles and brown spots, there is a more sinister side to sunshine.

Editor Trudi Brewer shares why a skin mole check is essential and how her last one was a wake-up call she didn't expect.

Editor Trudi Brewer’s mole removal

New Zealand is the place to be in summer, with the beaches, festivals, and easy, outdoor living, but the UV rays are punishing. Our sunshine is harsh, and burn time in high summer can happen within 15 minutes. To put that in perspective, New Zealand's peak UV levels can be up to 40 per cent higher than at similar latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. Another reason sunscreen is crucial daily, even in cloudy, overcast weather. Add to that our thin ozone layer, which absorbs less of those harmful ultraviolet rays, and low air pollution, thanks to our sparkling, clear skies, it’s no wonder we have some daunting stats around melanoma. In the hope of spreading awareness, style director Louise Hilsz and I went for a skin mole check, and while one of us sailed through, I was not so lucky. Monitoring your moles can feel overwhelming, but staying informed and understanding the risks empowers you to protect your skin health. Despite being diligent and self-checking, I still needed surgery to remove a mole that wasn’t exposed to the sun. Here, two top skin cancer specialists share sobering facts about melanoma and the importance of annual mole checks, along with my anxious days spent awaiting mole-removal results. Read on to learn more, by editor Trudi Brewer.

Nurse, Katy Doherty, founder of Espy Skin

Nurse, Katy Doherty and founder of, Espy Skin, in Auckland

With over 30 years of experience as a New Zealand Registered Nurse, Katy Doherty, founder of Espy Skin, is well-versed in all aspects of cancer surveillance. She has a relaxed bedside manner to make sure everyone feels comfortable and confident.

What do you look for when checking the skin?

I use both visual inspection and dermoscopy. A dermatoscope improves diagnostic accuracy by magnifying and illuminating the skin to reveal hidden patterns and clues invisible to the naked eye. I look for changes in colour, size, or shape, especially after the age of 40; unusual borders; multiple colours; and raised nodules and ulcerated lesions. Not all moles are melanoma. Most moles are happy, harmless, and remain stable, but 30 per cent of melanomas can arise in an existing mole, versus 70 per cent arising as a brand-new mole.

How often should you self-check?

You should perform a self-skin check at least once every three months, though monthly is also often recommended to establish a good habit. During a self-check, check your entire body, including the scalp, soles, nails, and back. Look for new or changing spots, and if you find anything suspicious, have it reviewed by a professional promptly.

Where is melanoma most commonly found on the body?

On the back in men, and on the legs in women. Which means they are often behind us, in places hard to see on our own. Melanoma can develop anywhere on the body, including the face and arms, and at less common sites such as the soles of the feet, the palms of the hands, and under the fingernails and toenails — even in areas never exposed to sunlight.

Doctors refer to the alphabet when checking, A to G. What are these?

A- Asymmetrical: Is the mole asymmetrical, with two halves of the lesion that don’t match if you draw a line through the middle? B-Borders: Are the lesion borders ragged or irregular? C- Colours: Does the lesion have more than two shades of colour? Melanomas can have different colours, including browns, blacks, pinks and grey. D- Different: Is the lesion different from your other moles, or does it have a diameter greater than 6mm? E- Evolving: Is the lesion changing in size, shape or colour or becoming elevated like a nodule? F- Firm: Is the lesion firm to the touch or painful? Finally, G- Growing: Means the lesion is growing, getting bigger, or spreading.

There is also a BB rule for melanoma?

The BB rule is a simplified public health message meaning “Black and Brown, Beware.” Which refers to lesions with uneven black or brown pigmentation, especially new or changing ones, require professional evaluation. Like the saying for clinicians, Pink and Brown make us frown: If we see lesions that dermoscopically show pink and brown, we become suspicious of them.

Editor Trudi Brewer’s suspicious mole that needed to be removed.

How often should you have a skin check?

You should get a professional skin check at least once a year, though this may vary depending on your skin type and risk factors. Those with higher risk factors, such as a history of sunburns or fair skin, family history of melanoma, many atypical moles, or outdoor work, may need more frequent checks every three to six months. Consistency is more important than season; melanoma can appear at any time of year.

With the recent controversy around SPF ratings and brands, can we trust?

All sunscreens sold on the NZ market should meet their SPF claims, as labelled on their packaging, under NZ regulations and guidelines. You can check on the Consumer NZ database. I personally choose reputable brands that I know I can trust. International brands like Avène and La Roche Posay are great and adhere to regular testing. Additionally, New Zealand brands Ed&i, My Sunshine, and Skinnies, as well as Australian-made Solarcare B3, have been my go-to products for the last few years. They have all conducted independent testing and have consistently met their SPF claims.

What is the one sunscreen myth you would like us to ignore?

That you don’t need sunscreen on cloudy or cool days, New Zealand’s UV rays can be dangerously high even in winter - up to 40 per cent of UV radiation penetrates cloud cover. Sun protection should be a year-round habit, not just for summer.

skin cancer expert, Dr Andrew MacGill of skincheck

Dr Andrew MacGill from Auckland’s Skincheck

For skin cancer expert, Dr Andrew MacGill, from Skincheck, medicine is in his DNA. His great-grandfather, grandfather, and father were all GPs; his son is also a doctor specialising in surgery. He is a highly experienced and well-regarded doctor himself, and he is an expert in all forms of skin cancer, including detection and cutaneous surgery. He regularly shares his knowledge with other doctors here and offshore. Here, he shares the facts on melanoma and why we have one of the highest rates in the world.

Why do we have the highest death rate of melanoma in the world?

New Zealand’s high mortality rates are due to our high incidence of melanoma and, historically, due to the lack of access to modern life-saving therapies. New Zealand is consistently ranked with Australia as having one of the highest rates of melanoma in the world. It’s a perfect storm of factors: Extreme UV radiation, our clear air, and proximity to the hole in the ozone layer (though it is recovering), which means the sun's UV radiation is extremely powerful here. We get about 40 per cent more UV than similar latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.

A significant part of our population has fair skin, which is less adapted to intense UV radiation. Finally, that "She'll Be Right" attitude, we have a strong culture of being outdoors, often with a casual approach to sun protection. Excessive UV exposure, especially intense, burning sun exposure during childhood, is the major cause. This last point is very important for all parents to be aware of.

Has our historical lack of access to modern medicines in NZ had a significant impact on mortality compared to other Western countries, where these therapies are funded?

For years, New Zealand melanoma patients had slower and more restrictive access to the revolutionary cancer drugs available in countries like Australia, the UK, and the US. The new class of drugs (immunotherapies like Pembrolizumab/Keytruda and targeted therapies like Dabrafenib and Trametinib) dramatically transformed the prognosis for advanced melanoma, often turning a terminal diagnosis into a manageable chronic condition for a significant number of patients. Because New Zealand patients often had to wait or self-fund these incredibly expensive treatments, their survival rates for advanced-stage disease were considered unacceptably low compared to our international peers. In short, while our high melanoma rates are primarily due to sun exposure and fair skin, the mortality rate was likely exacerbated by the delay in providing funded access to the best modern treatments for those with late-stage disease.

Has the recent announcement by Pharmac changed this?

Yes, the recent, significant funding announcements by Pharmac are a genuine game-changer. The funding, particularly for immunotherapies (such as the expanded access to Keytruda) and the new funding for targeted therapies (Tafinlar and Mekinist for the specific BRAF mutation), has brought the standard of care for advanced melanoma in New Zealand much closer to international best practice. For stage IV (metastatic) patients: These drugs offer a chance for long-term survival that simply did not exist a decade ago. We have already seen a statistically significant decline in New Zealand's overall melanoma mortality rate in the years immediately following the initial funding of these advanced immunotherapies, which experts believe is directly linked to their availability. For stage III patients (adjuvant therapy): Critically, the wider funding now includes using these treatments after surgery (called adjuvant therapy) or before surgery (called neo-adjunct therapy) for stage III and certain stage IV melanomas. This means these drugs are being used to stop the cancer from ever coming back or spreading in the first place, potentially curing many more people and dramatically improving the long-term outlook for hundreds of New Zealanders each year.

How does a mole develop into melanoma?

Melanocytes are throughout your skin and produce melanin when exposed to UV radiation (this is why you get a tan). When melanocytes are in clusters, they form a mole. Melanoma starts when the DNA in these melanocytes becomes damaged, often by UV radiation, and begins to grow out of control. Ageing is also associated with DNA damage, which is why the incidence of melanoma increases with age. Around 70 per cent of melanomas appear as a new spot on your skin. About 30 per cent of melanomas develop within an existing mole, changing its appearance. It's a slow process that starts at a cellular level, which is why catching changes early is so vital.

How many moles that you see are diagnosed as melanoma?

This is an important perspective to have. Most moles are completely harmless. For a dermatologist or skin cancer specialist, the vast majority of spots they look at are normal or benign (non-cancerous). Only a tiny fraction of the suspicious spots a patient is worried about turn out to be melanoma. That said, if you spot a concerning change, it's always worth a check-up. Having a large number of moles is the highest risk factor for developing a melanoma. Someone with over 100 moles has about a seven-fold increased risk compared to someone with less than 20 moles.

Why does a mole need to be removed and leave a scar to determine if it is or is not melanoma?

The only way to definitively diagnose melanoma is to examine the suspicious cells under a microscope. A skilled pathologist must examine the entire thickness of the removed mole to answer two critical questions: Is it cancer (melanoma)? If it is cancer, how deep has it grown? (The depth, or 'Breslow thickness', is the single most important factor for determining a patient's prognosis and next steps.) A mole has to be fully excised (cut out) with a small margin of skin to get this accurate reading. We simply cannot tell for sure by just looking, even with powerful magnifying tools. The scar is a small price to pay for a confirmed, often life-saving, diagnosis. Currently, there is no single blood test used for the routine diagnosis of early-stage melanoma. However, there is research into this.

Can melanoma show up on areas of the body that are not exposed to the sun?

Yes, absolutely. While over 95 per cent of melanomas are linked to UV exposure, melanoma can appear anywhere, including the palms of your hands, soles of your feet, and under your nails (people with darker skin are more prone to melanomas in these areas, but only at the same incidence as lighter-skinned people). Sadly, Bob Marley died of a melanoma under his toenail. He thought it was a bruise from kicking a football. Your eyes, as well as mucosal surfaces such as your mouth and genital areas, are also to be inspected. This is why regular, full-body skin checks with a trained dermoscopist are so important.

How long before melanoma metastasises? Where is the first place it spreads?

The time it takes to spread (metastasise) can vary hugely—from many years for very slow-growing types to sometimes just months for aggressive types. If an early-stage melanoma is successfully removed, the risk of recurrence is very low. If it has spread before removal, it usually presents within the first one to three years after the initial diagnosis. The first place melanoma often spreads to is the nearby lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are found throughout your body, but are more prominent and more easily examined around your neck, armpit and groin. These little bean-shaped glands are part of your body's immune system and act like a filter, which cancer cells can get caught in. If melanoma spreads beyond the skin and nearby lymph nodes (Stage IV), it can travel through the bloodstream and affect almost any organ. The most common sites are the lungs, liver, brain, and bones.

Is melanoma hereditary?

Melanoma is not strictly hereditary, but genetics play a role. Most cases are sporadic, meaning they arise from sun damage and not an inherited gene. However, about 10 per cent of people with melanoma have a close family member who also had it. If you have two or more first-degree relatives (parent, sibling, child) with melanoma, your risk is significantly higher, and you should be especially vigilant with sun protection and skin checks.

What are the survival rates?

Survival rates depend entirely on the stage at which the melanoma is caught: If caught very early (Stage I or less), the five-year survival rate is exceptionally high, over 95 per cent. This is why early detection is so important. For melanoma that has spread to nearby lymph nodes (Stage III), the five-year survival rate drops significantly. For melanoma that has spread to distant organs (Stage IV), the outlook is more challenging, but new drug therapies are dramatically changing these numbers. The difference between a melanoma caught early and one caught late is literally life and death.

Experts Trust these sunscreen brands

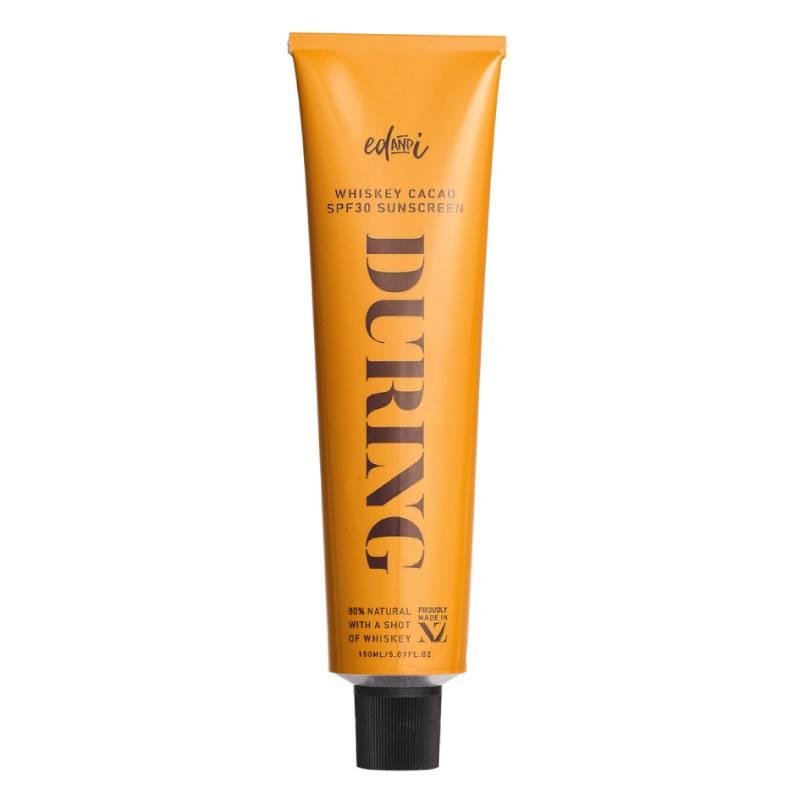

Avène Cicalfate+ 50 Multi Protective Restorative Cream SPF50+, $40. La Roche-Posay Anthelios Mineral Tinted Ultra Light Face Sunscreen Fluid SPF 50, $42. SolarCare B3 Cream,$75. Ed&I Body During SPF 30 Sunscreen, $52.

Editor Trudi Brewer shares her experience with a melanoma scare. Watch the procedure below

In my 20s, I was a bikini-loving sun bunny who couldn’t get enough of summer. My mum encouraged tanning—she was always a deep bronze, thanks to generous amounts of coconut oil, and for years I followed her example. However, in my late twenties, my career in journalism made me aware of just how dangerous and damaging UV rays are to the skin. Not only do they accelerate ageing, but they also undermine the benefits of good skincare and cosmetic treatments. There is only one proven anti-ageing solution: a broad-spectrum SPF 50+. While I still adore summer, I’ve swapped sunbathing for self-tanner and am committed to daily SPF. Yet, I carry the legacy of my sun-soaked youth — in moles. For two decades, I’ve had regular mole checks—usually every two years—and have never had a suspicious result—until now. Back in October, in support of Melanoma Awareness Month, our style director and I decided to get our moles checked to raise awareness. She passed with flying colours; I was not so fortunate. Our visit was to Espy Skin, where the founder and nurse Katy Doherty examined us both. She noticed that a mole on the left side of my lower back—one I’d had for decades—had recently changed colour and grown. When she called me hours later, recommending its removal, I felt a surge of anxiety. Even though I’ve written about melanoma for years and am vigilant with self-checks, it’s impossible to monitor every mole for subtle changes, especially those you can’t see. Doherty suggested Skin Check in Takapuna, Auckland, for the removal, and I was quickly scheduled to see Dr Andrew MacGill four days later. Now it’s at this point that my knowledge was vague. I expected a tiny incision and a Band-Aid, but it’s not that straightforward. The suspected melanoma was removed under local anaesthetic using a wide excision—a procedure that takes the mole along with a border of healthy skin to minimise the risk of recurrence. This is the standard approach for mole removal, as it allows both the mole and the surrounding skin to be tested. The procedure is usually done as an outpatient under local anaesthetic. The width of the margin taken depends on the thickness and size of the mole; thicker moles require a wider border (mine cut was about two centimetres, or the size of a small Brazil nut). If the mole turns out to be melanoma, a larger area of skin may need to be removed to ensure the cancer hasn’t spread. Dr Andrew MacGill put me at ease with his expertise and precision. The procedure itself was swift. Post-surgery, the pain was mild stinging, but persistent. The most frustrating part was avoiding bending and skipping Pilates for two weeks, but the real challenge was the anxiety as I waited for my results. After four anxious days, I received the news that the mole was benign—and I was deeply relieved.

Still, having a suspicious mole was a wake-up call. I’m vigilant with sun protection now and never sunbathe, but every mole holds a memory of the past. While I no longer take risks with the sun, my younger self did, and my moles are a reminder of that. This new scar is a permanent badge, a reminder of the importance of regular skin checks.

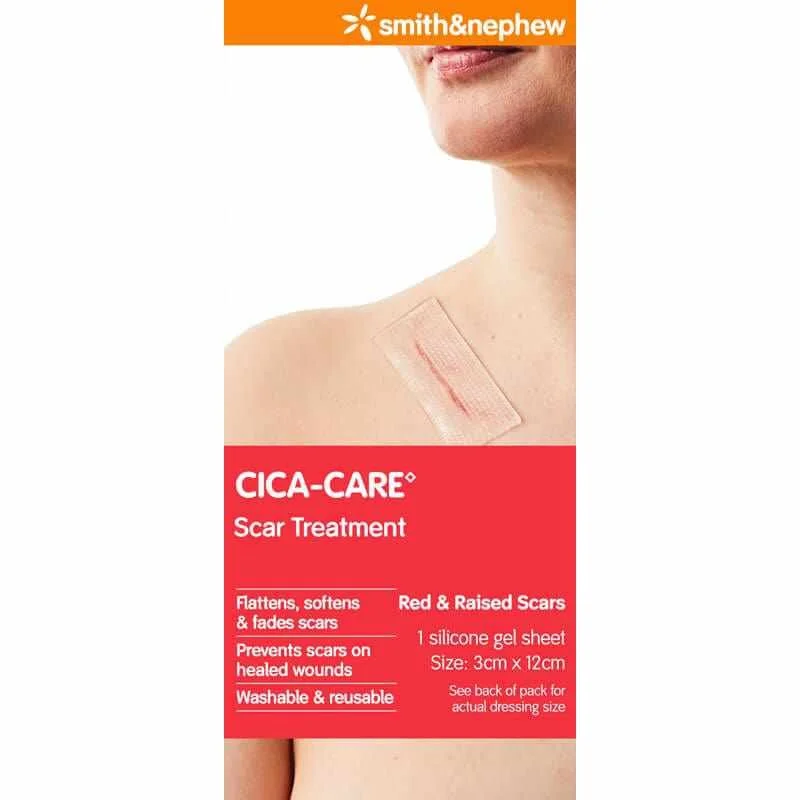

I’m following the best scar practice, and now that the wound has healed, I’ll tape the scar for six months, reapplying every few days. Keeping the tape on 24/7 keeps constant pressure on the scar and helps flatten it. Then, in six months, I’ll use scar gel and massage.

To quote Louise Hilsz, ‘your bikini days are over,’ and she’s right, but more importantly, I have a clear result, and I’m grateful the scar isn’t on my face.

My takeaway: be vigilant about mole checks, stay covered when outdoors, and remember there’s no better prevention or anti-ageing protection than an SPF 50+ sunscreen. Use it every single day—not just in summer. Find a formula you like to wear and make it a daily habit; it will help prevent wrinkles, dark spots, and, most importantly, could save your life.

The list of what we are taking and why.